BLOG: A History of the World Cup in Ten Objects Part Two: The First Official World Cup Mascot,Willie

In the second of three blogs, Professor of Sport Jean Williams looks at some of the artefacts that feature strongly in the history of the World Cup.

Family audiences ‘The family at home’ unprecedented marketing

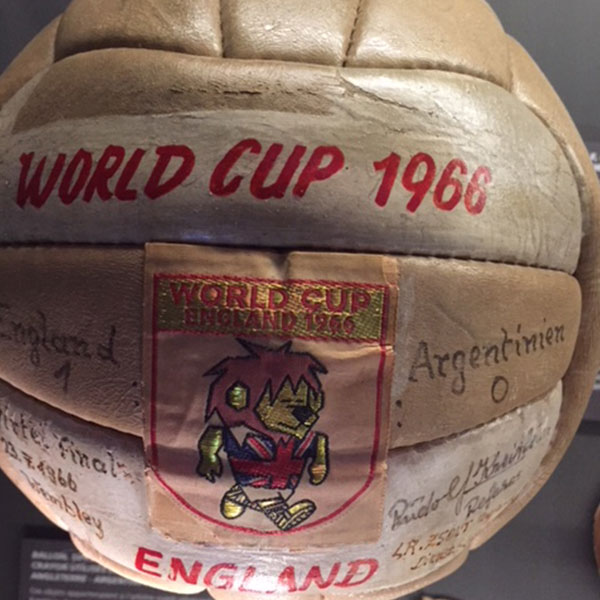

The big point about 1966, and it seems that the first World Cup mascot, World Cup Willie cannot be over-estimated in this regard, is that it reached out to a family audience through an unprecedented degree of commercialisation. The mascot effectively unfixed merchandising from being strictly about the football and made a story about a plucky, optimistic, confident cartoon character. Importantly, Walter Tuckwell Associates thought the original FA mascot too boring, and, based on their other expertise with promoting Dr Who, Noddy and other character mascots they designed something that was a bit naff but not much more naff than Mickey Mouse or Warner Brothers character cartoons. The humour, and the slightly home made properties of Willie offset the huge pressures of hosting a World Cup in the country that had codified football over one hundred years before.

So the social history of 1966 is not just about who made it into the stadium or what the score was, or even whether the ball did cross the line but targeted children and youths, and people who might buy merchandise for them.

By the early sixties forty per cent of the population was under 25 years of age. At the time when people owned their first television and then first colour televisions, the mascot helped to bring football into the living room. There is a nice inter-generational aspect to this: were Gran and Grandad and a few cousins there too?

The family at home was targeted because they could consume football while consuming other goods and services. Vesta freeze-dried curries were released in the mid 196os as a kind of ‘exotic’ fast food, like US TV dinners. Kentucky Fried Chicken opened its first UK store in Preston in 1965.

Reg Hoye and Richard Culley designed Willie, originally based on Reg’s son Leo Hoye but later changed from a boy to a lion. This anthropomorphosis helped to sell the lion to girls as well as boys.

Women’s football was still ‘banned’ by the Football Association at this point, and internationally neglected by FIFA. By 1969 this would change, slightly, to tolerate women’s football. The FA did not really promote football for women and girls until 1993. However, many women and girls were in evidence as fans in 1966 and many were inspired to take up football as a result of England’s win.

‘Windrush Generation’ and the African boycott

In 1947, India split from Pakistan forcing millions of people to leave their homes in search of safety. The British Nationality Act 1948 gave British citizenship to all people living in Commonwealth countries, and full rights of entry and settlement in Britain. The ship MV Empire Windrush brought the first group of 492 Afro-Caribbean immigrants to London on 22 June 1948. There was plenty of work in post-war Britain and industries such as British Rail the National Health Service and public transport recruited almost exclusively from Jamaica and Barbados.

However, the economic conditions of 1966 were very different and by this time many of those who had migrated had children, a first generation of British-Asians or Black-British citizens. In the context of this, the 1966 World Cup was boycotted by 17 African nations in protest at the limited number of berths for African, Asian and Arabic countries. I don't know if anyone has ever done a specific project asking what the Black and Asian communities though about this (please get in touch if you have), but at the time England hosted the world cup it was a more diverse country than before 1945, partly in respect of the contribution of Commonwealth countries to the war effort and also the new economic conditions of peacetime. As a result, Ben Carrington and other academics have called the sporting-diaspora effect that many Black-British fans felt that they had more affinity with the multiracial Brazil team, than with the England team. Paul Campbell has also shown how the 1970 Brazil team directly inspired the formation of a local club in Leicester, Cavaliers, who wore yellow Brazil-style shirts.

World Cup Families of the Players

Unfortunately not all of the players in the squad are still with us, and even if they were, there resides in their family a wealth of memories about what it was like to actually win the thing.

If you know Dil Porter’s article ‘Egg and Chips with the Connelly’s’ a lot of the players were able to drive themselves home and had some fairly basic celebrations after the initial receptions. The wives were famously not invited to the official celebration by the FA and went to a nearby restaurant instead.

Football was very different event in 1966 with the end of the retain and transfer system and wage caps. Bobby Charlton’s autobiographies and those by Bobby and Tina Moore’s show it affected their lives, in terms of intense pride but not economically right away. It’s an interesting contrast that George Best became the ‘fifth Beatle’ in 1966 with his astounding performance against Benfica in the European Cup, scoring two goals at the Stadium of Light to give Manchester United victory. By 1968, he would personify the youth culture that we associate with elite football today, and also, perhaps its excesses.

Again, the lives of the victorious England players was much closer to the average family then and points about family life (houses, cars, music, food, clothes etc) can be useful for re-thinking the stereotype of the swinging sixties. It wasn't universally swinging even in 1966, or by the same token 1968, if for some, it ever swung at all. So you can have a daft little mascot in a Union Jack waistcoat which can make broader points about the changing social history of the time.

- Jean Williams is Professor Sport and part of the University of Wolverhampton’s Institute of Sport and Human Science. She also works closely with the National Football Museum in Manchester.

For more information please contact the Corporate Communications Team.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/iStock-163641275.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/250630-SciFest-1-group-photo-resized-800x450.png)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/210818-Iza-and-Mattia-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Maria-Serria-(teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/210705-bric_LAND_ATTIC_v2_resized.jpg)