BLOG: A History of the World Cup in Ten Objects, part 1

In the first of three blogs Professor of Sport Jean Williams looks at some of the artefacts that feature strongly in the history of the World Cup.

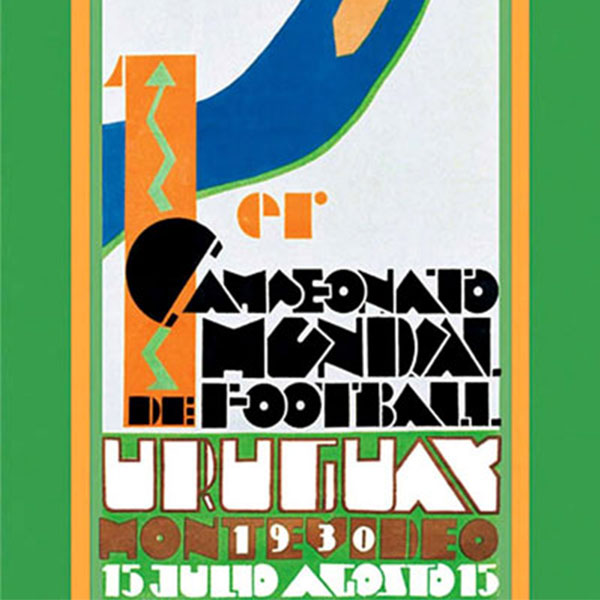

The 1930 World Cup Poster

From a historical perspective, World Cup posters provide a fascinating record of the growth of the world’s most popular sport. For the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup, posters have been a primary means of visual communication since the early twentieth century. FIFA had been founded in 1904 without the benefit of British attendance. With the success of the Olympic football competition between national sides at the London 1908 Olympic Games, friendly international rivalries were popular with fans and the media alike. Because these were amateur events, not all countries could send their best squads. From the original six teams in 1908, twelve national teams played at the Stockholm Games in 1912 and England (or Great Britain) beat Denmark on both occasions.

In 1914, FIFA agreed to recognise the Olympic tournament as a world football championship and took responsibility for organising the event. This, and other tournaments such as the La Stampa Sportiva tournament the same year, and the Lipton Trophy in Turin in 1909, led the way for the world's first intercontinental football competition at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, involving fourteen teams including Egypt, won by hosts Belgium.

Uruguay convincingly won the tournaments in 1924 (22 teams) and 1928 (17 teams) and although these would involve more nations than the first world championship the key issue was that professionals could compete. Rivals to host the first FIFA World Championship included Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain and Uruguay.

Although posters had been integral to the wider awareness of the Olympic Games, the World Cup developed its own aesthetic from 1930 onwards. Posters could be understood by those who did not necessarily speak the language of the host country.

They could be read both as straightforward announcements of a forthcoming tournament but also as complex metaphors for the host nation and football as an increasingly global cultural industry. There were consequently both international and domestic audiences for a particular design; on the one hand the host country defined, projected, and invited an international audience to participate in their festival of football. On the other hand, regional stakeholders of various kinds had to be involved as paying spectators; to provide, and often build, local venues for the games, and as supporters of the national team. The poster was therefore simultaneously a medium for local, regional, national and international publicity. What values and aspirations have posters signified? How have the design features of the graphic presentation shaped the identity of the World Cup over time?

1930s Design and Art

This is a geometric, abstract and fragmented often with jarring colour ways to evoke the dynamism of modern urban culture. Combined with Hollywood glamour, itself a response to the deep Depression of the 1930s, it came to represent new aspirations and desires, notably the search for youth, glamour, fantasy and fun. Arguably, by the 1930s the poster can best be understood as an artistic and symbolic statement than of practical use, since fans of movies, sport and so on had long been able to find out the date, time and place of events from other sources. The World Cup poster has therefore been used as an artistic medium when its practical purpose had often become virtually redundant. However, they were a relatively cheap and highly evocative form of advertising. So what do we know about the official posters?

Uruguay in 1930 (Centenary Stadium newly built to celebrating 100 years of independence)

Designed by local artist Guillermo Laborde in a competition, this is one of a handful of posters to focus on the goal-keeper as the strong diagonal motif rising, almost transcendent, to the top corner of the goal. Strong influences of Art Deco which, from 1925 onwards signalled commerce, capitalism and communication. An art form which celebrated geometric and angular shapes, it coincided with the expansion of mass tourism and luxury travel offering images of modern life and progress. Red was a particular favourite of many designers and the zig-zag arrow was typically dynamic. A small country of 2 million people in 1930, this poster is now treated as a national treasure and an original painting in their national museum was treated to careful restoration recently. The image has been subject to reproduction on a number of items from statues to pin badges, and silver & enamel medals for the 1930 World Cup finals by Stefano Johnson of Milan, the obverse enamelled after Guillermo Laborde's official poster design.

- Jean Williams is Professor Sport and part of the University of Wolverhampton’s Institute of Sport and Human Science. She also works closely with the National Football Museum in Manchester.

For more information please contact the Corporate Communications Team.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Diane-Spencer-(Teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240509-Menopause-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Maria-Serria-(teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240315-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/BDA-group-photo.jpg)