Something borrowed

A blog post written by Josiane Boutonnet, Dr Esther Asprey and Judith Hamilton from the English language/linguistics team on loanwords as the UK moves into the pre-election period for local elections, also commonly referred to with a borrowed word...

It goes without saying that every language that people use changes over time. English has borrowed many thousands of words from other languages since its infancy. We use the term borrowing to refer to the process whereby words are adopted from another language. It is worth noting that loanwords do not always occupy the same semantic space, meaning that when we borrow a word, we may use it in a slightly different way to the way it is used in the other language. Compare English <dead end> with French origin <cul de sac> for example and you will see that they do not mean exactly the same thing.

It is possible for a loanword to be used in a more specialised way for example, and be applied to a reduced domain of use. So for example, the word <cattle> and the word <chattel> both originally meant ‘goods’, ‘wealth’ but the first, borrowed from Norman French, has come to mean wealth in the form of cows, where the second, borrowed later from Central French, still means something like wealth in a more general sense.

In the process words can also lose their original connotations, and language users may over time be ignorant of those. So many of our words in English have been borrowed that much of the time the foreign flavour is completely lost on us.

The word purdah is a loanword which in English describes the pre-election period, and the way civil servants must operate, with political neutrality. The Oxford English Dictionary tells us it is partly a borrowing from Urdu, and partly from Persian. In Urdu, parda denotes a curtain or veil, and one used in some Muslim and Hindu communities to screen women from public observation, particularly the sight of men or strangers. Harini Iyengar, barrister and candidate on the London wide list for an Assembly seat in the forthcoming election, claims that using the word purdah is ‘sexist, racist and offensive’. Her argument is that the word has been misappropriated during the British Occupation of India. The word refers to a system that took away women’s human rights.

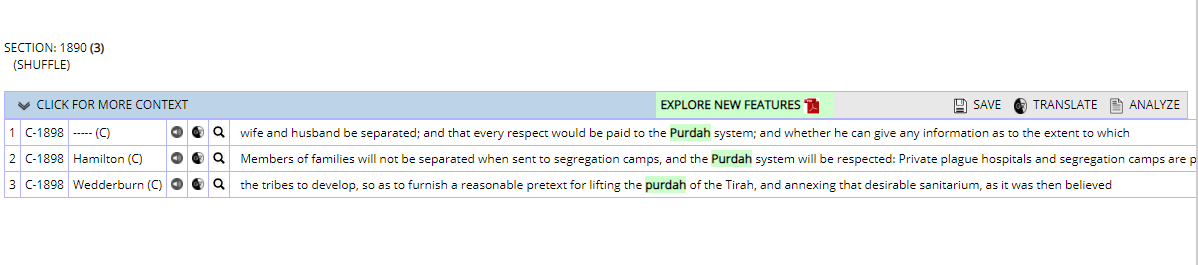

It first appears in Parliamentary discourse in 1898, and the three hits we see in that year clearly refer NOT to the ban on discussing politics pre-election but to the purdah system itself in British India:

Of course, language users can also eventually extend meanings to other situations, and in English the word can be used in a more general sense to refer to anyone who is isolating themselves, such as the example given by the Cambridge English Dictionary: Jeff has gone into purdah while he's preparing for his exams. The Oxford English Dictionary claims this last meaning to be in extended use, implying a degree of secrecy is involved, and gives the example: The Chancellor retreats into purdah and everyone tries to guess what he will announce.

Interestingly though, this transfer of the sense of physically separating women from men to the sense of keeping information separate from others does not appear in UK political discourse until 1951 when the first metaphorical use of the term appears in discussion of the Gas Undertakings Bill for Scotland:

“Nor do we today know whether any progress has been made in any of these matters, for under nationalisation the Minister coyly goes into purdah and any knock at the door of his seraglio to try to get an answer meets with no response at all.”

HANSARD https://www.english-corpora.org/hansard/

For linguists, discussions of loan words are interesting ways of investigating patterns of contact between groups of people as well as the cultural values of these communities. This includes debating the relationship between language and power and the way language can be used to represent groups in subjective ways. Taking a socio-historical perspective is important, as words change meaning over time, along with societal attitudes. Taking part in these debates can lead to linguistic intervention and change.

More importantly, talking about language can help raise awareness of the way people want to be addressed and events and actions are described.

For more information please contact the Corporate Communications Team.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Diane-Spencer-(Teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240509-Menopause-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Maria-Serria-(teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240315-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/BDA-group-photo.jpg)