No more hiding, embrace your individuality

Dr Debra Cureton, Associate Professor of Equality in Learning and Teaching, blogs about living with Dyslexia.

I love working in higher education, but it hasn’t always been a smooth ride, and for most of my career, I made choices that were based on navigating or hiding certain difficulties that I didn’t feel that I could be open about. I guess, these are disabilities, but my working-class childhood meant that I learned not to describe them as that, and to hide these so that I was seen as equally employable as other people.

However, now I am more comfortable talking about the conditions that I have, even if using the word ‘disabilities’ is alien to me. I am severely dyslexic and I wear green glasses to correct Meares Irlen Syndrome, which is a visual disturbance that often accompanies dyslexia.

Additionally, since childhood, I have lived with Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD). I also have two genetic conditions, the first is Lynch Syndrome which predisposes me to cancer, and the second is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) which means I have hypermobility and mild scoliosis. In addition to this, I struggle with Chronic Fatigue and was diagnosed with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) in the mid-1990s. Finally, I only have 10 per cent sight in my left eye.

I have learned to live with many of these conditions. However, feeling that I had to hide my dyslexia, manage the high functioning anxiety that accompanied C-PTSD, and the constant pain and tiredness that results from ME, meant that I made ‘careful’ career choices.

When I finished my doctorate, I did not head straight into teaching like many of my peers did. Anxiety robbed me of the pleasure many people experience when they teach; speaking in front of hundreds of people was plagued with fear, stress and self-doubt. Dyslexia also created a fear of having to put words on to slides when I might not see a mistake I’d made, and forgetting simple words when teaching, which would leave me feeling humiliated.

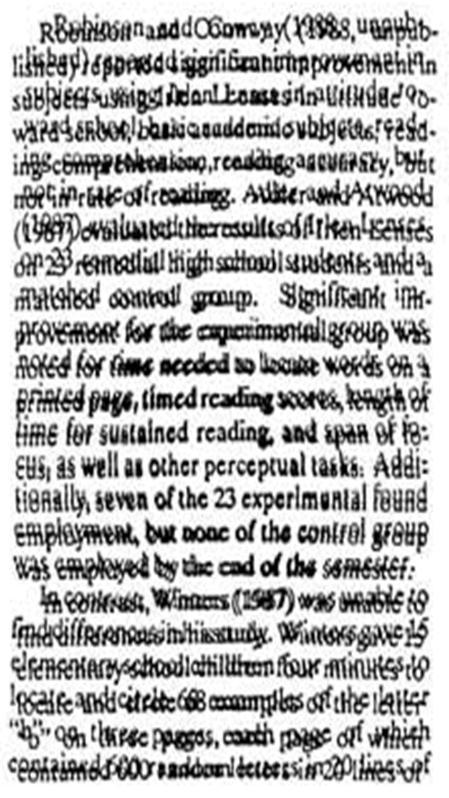

The thought of marking was nightmarish. It is so important to read what a student has said rather than what you think a student might have written. When you are dyslexic, it is easy to misunderstand the written word, especially when what you see on a page looks something like this. Being constantly tired and in pain also generated a brain fog that exacerbated the word aphasia that I experience and doubled the amount of anxiety I experienced when having to speak to others. I tended to only speak if it was important, and as a result people often thought that I lacked drive or wasn’t astute.

Instead of lecturing, I decided to stay in research where I felt safe, and able to hide. Dyslexia may mean I struggle with certain things, but neurodivergence also means that I am stronger in some areas than other people. I have strong systems thinking abilities, I think outside of the box, I am an extremely efficient problem solver, and I am highly innovative. All of these are the fundamental skills of a good researcher. So, I thrived in a research environment. The only problem is, that research has little career progression opportunities. You can become a reader or professor, but it takes years to get to that stage. Research roles are often short-term contracts which research shows negatively impact on a person’s career trajectory. Unlike lecturing, where you can transition from Lecturer to Senior Lecturer, a similar progression doesn’t happen for Research Fellows. Senior Research Fellowships are rare and must be applied for. Needless to say, I didn’t make much career progress from the safety of my researcher role.

Had I not chosen to hide my difficulties, career progression could have been more readily available to me. Having spoken to other people who hide their difficulties, it is quite apparent that we do this because we fear others’ judgement. We fear that it will be detrimental to our job safety or in case we are viewed as not being promotion material, and in doing so, we can block our own progress if the organisation that we work for is not clear about how it values the diversity of its staff.

Recently, I have joined the Disabled Staff Network at the University. In fact, I joined the Neurodiversity Support Group to start with. I soon realised that the Network is a supportive and facilitative group of people who help each other navigate difficulties and support each other as we do that. I wish I had felt the fear and done it earlier. If I had, my career might have been very different.

As part of their work, the Disabled Staff Network has generated the Disabled Equity Action Plan (DEAP), which is sector leading. DEAP is like Athena Swan and the Race Equality Charter but focuses specifically on supporting those with disabilities to be able to grow to their full potential at the University of Wolverhampton and to help build a stronger community.

It is my sincere wish that the DEAP will encourage others to have confidence that although aspects of their chosen career might be difficult, the University understands and is committed to supporting all staff to fulfil their potential.

Find out more about how to get involved in Disability History Month

For more information please contact the Corporate Communications Team.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Diane-Spencer-(Teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240509-Menopause-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Maria-Serria-(teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240315-Research-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/BDA-group-photo.jpg)